Yume Nikki (Kikiyama, 2004) Review

Wandering in a feverish exhibition of dreams that refuses to be played.

As fascinating as dreams are, they are relatively under-explored in the medium of video games, which, along with film animation and literature, is the most appropriate medium to portray this subject due to the lack of physical constraints to represent abstract ideas. Yume Nikki is one of the few well-known titles in this category, along with the PSX game LSD: Dream Emulator, released in Japan in 1998. The influences are obvious, even more so considering that Kikiyama, the Japanese creator, claimed to have played it in this interview. However, Yume Nikki’s approach to dreams is quite different from its potential source of inspiration, being darker, more abstract, 2D, and with tinctures of psychological horror.

The game’s title, which translates as “Dream Diary”, effectively captures its concept, as we explore the scattered dreamscapes of the protagonist, whose name is not explicitly mentioned. In fact, there is no dialogue or written word, except for a kanji on the floor of a certain area. There’s also no combat, and no apparent plot or goals to achieve beyond collecting items called effects, useful for unlocking some areas, and wandering around the world, which fits the vague sense of dreams and their apparent lack of meaning.

The actual experience of playing it feels like a trip: you think better of it when it’s over. Yume Nikki’s simple exploration mechanics are acceptable at first, but they come back to bite you once you find yourself desperately wandering around the same places, looking for more areas and secrets to discover. The bare gameplay mechanics are a double-edged sword, as the world and the freedom to explore it are a big part of what makes this game special, but the lack of guidance makes it a drudge to play. The positive energy of having a genuine curiosity to explore every nook and cranny of the world fades as soon as you start passing by the same places over and over again, trying to find more zones and effects to collect. In fact, as much as I hate using guides in games, I had to resort to one because I don’t think I could have seen everything in a reasonable amount of time on my own. By the point I had to do that, I was already bitter about the title, so I didn’t enjoy the rest of the zones I hadn’t explored as much, because it felt like a long slog to get to the end.

In this respect, it makes complete sense that the current version of the game is 0.10, which was released in 2007. It feels like a blueprint that lays out the basic structure of the game to further refine the gameplay mechanics in future updates, which unfortunately didn’t happen in the end.

I even considered the mechanics to be intentionally obtuse, like a self-defense mechanism to keep the player away from Kikiyama’s more intimate dreams (and perhaps some traumas). It feels more like a personal work rather than a video game intended to be played by many people, so it’s no coincidence that we know so little about the creator and his enigmatic Internet persona, given the introspective and mysterious nature of his only online creation. However, this doesn’t justify the soporific interaction between player and game.

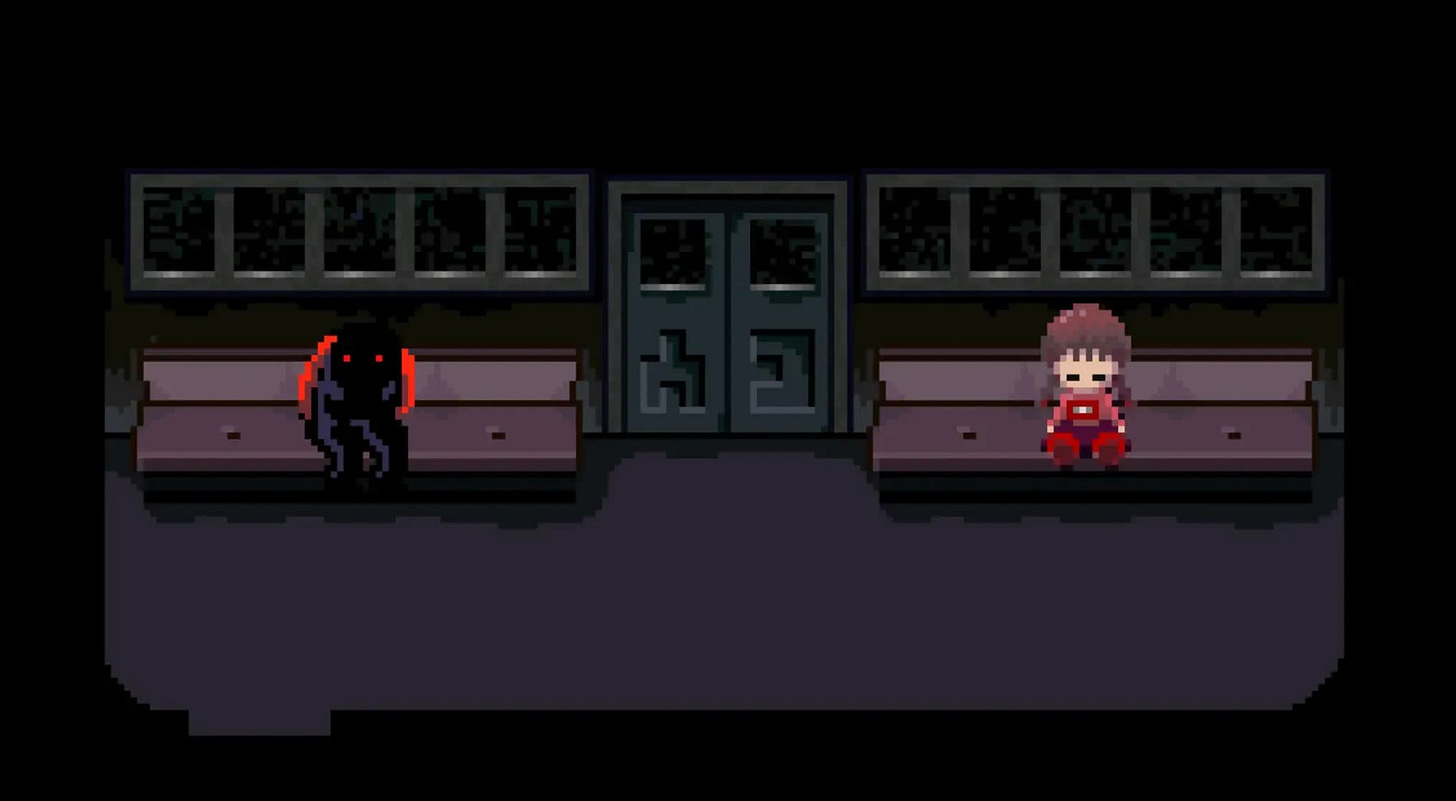

Every other aspect of Yume Nikki, aside from its playability, is quite fascinating, which is what kept me interested in exploring its ethereal depiction of dreams (though not so much towards the end). The surreal art, mysterious atmosphere, variety of zones, and brilliant soundtrack are all quite appealing, though my favorite of these is the latter, which accurately captures the Gen Z zeitgeist with traces of emotions such as melancholy, nostalgia, sadness, confusion, and tension. Each track has a different vibe to match the zone in which it is played, based mainly on 8-bit chiptunes reminiscent of some Pokémon and Earthbound tunes, as well as some dark ambient tracks.

Here is a Spotify playlist with my favorite ones:

In retrospect, it’s striking that Kikiyama’s creation was originally released in 2004, because it doesn’t feel dated at all. It left an indelible mark on the indie landscape, influencing other titles like Undertale, OMORI, and the RPG Maker games that came later. Furthermore, it has had such an impact on its players that it has inspired the development of numerous fan games based on it. I’m looking forward to playing some of them, such as .flow and Yume 2kki, because I like the idea behind Yume Nikki and I have faith that other people’s creations will make the concept more playable.

Whether you’re among those players who were left with a lasting impression after exploring its ethereal dreamscapes, those who abandoned the game due to its dull playability and apparent lack of purpose, or perhaps somewhere in between, Yume Nikki undeniably remains a work that continues to fascinate and inspire, serving as a testament to the power of video games as a medium for personal expression and artistic exploration that transcends conventional notions of meaning.