The Substance (Coralie Fargeat, 2024) Review

A dark satire with wasted potential that made me cry of laughter

Warning

Spoilers ahead.

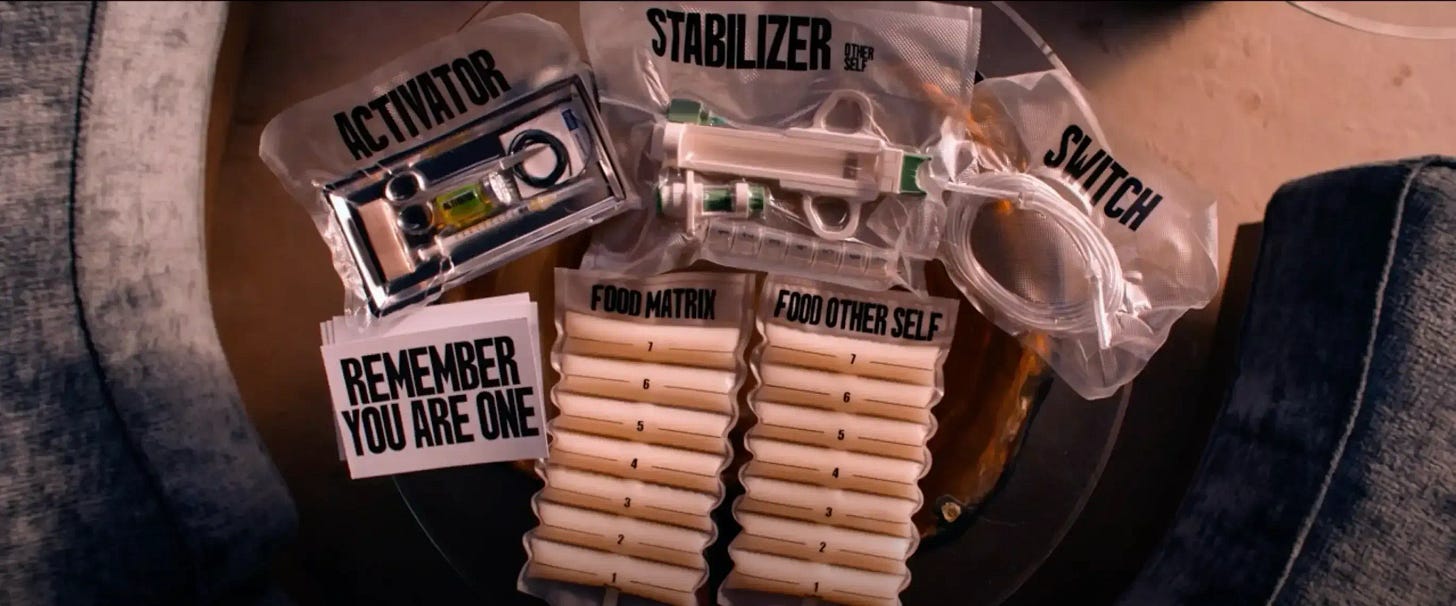

Have you ever dreamt of a better version of yourself? Younger, more beautiful, more perfect. One single injection unlocks your DNA, starting a new cellular division that will release another version of yourself. This is the Substance. You are the matrix. Everything comes from you. Everything is you. This is simply a better version of yourself. You just have to share. One week for one and one week for the other. A perfect balance of seven days each. The one and only thing not to forget: You. Are. One. You can’t escape from yourself.

The Substance is a black-market company that advertises its serum under the above premise. At the same time, it encapsulates the central concept of the film as an allegory for our fear of the spell of aging—as Anthony Kiedis would say—and the impact of ageism on female celebrities in Hollywood. The key condition of the product is that the two versions of oneself must establish a symbiotic relationship, as they must coexist in order to sustain each other. This implies that the core identity of the matrix remains inescapable, and that the quest for improvement must ultimately align with self-acceptance.

The primary consumer of The Substance in the film is Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore), a once-popular actress who now hosts an aerobics TV show—a role that draws clear parallels to Jane Fonda’s career, though Elisabeth never returned to acting. The turning point that drives her to succumb to the consumption of this product comes on her 50th birthday when she is abruptly fired from the show due to her age, though Harvey (Dennis Quaid), the producer, avoids explicitly stating the reasons. This causes Elisabeth to become distracted while driving when she sees a billboard of herself being removed, leading to a car accident that lands her in the hospital. There, a young nurse introduces her to the serum. After some initial hesitation, she decides to order and inject it, resulting in the birth of a younger, cellulite-free version of herself named Sue (Margaret Qualley), who emerges from a slit in her back—eerily similar to this scene in Alien: Covenant (Ridley Scott, 2017).

As advertised by The Substance, the consciousness of the matrix is transferred to the other self both during the body-switch and at the moment of splitting, known as activation. From the latter point on, however, each self retains its own recollection of their actions, without knowing that of the other self. This setup creates a compelling binomial of consciousness and memory that unfolds in a predictable (not a bad thing) reverse dynamic: as Sue’s fame and success grows, her concern for Elizabeth diminishes. So much so, in fact, that Sue suddenly becomes a professional do-it-yourselfer, building a PERFECT secret room in the bathroom to hide Elizabeth’s body—a mattress for her comfort wouldn’t have hurt.

Sue steps into the role of Elizabeth’s replacement, which she excels at. This arc reflects how men dictate the qualities women in the industry must possess, treating them more like a bag of meat than human beings, and how they impose an artificial expiration date on their success due to the waning of their flesh. This dynamic is further emphasized by the satirical juxtaposition of the ages of Harvey and the shareholders with those of Sue and Elizabeth.

Sue brings up to Harvey a “small scheduling issue” that causes her to be out of town every other week to take care of her mother. Harvey tells her that they will work around anyone she needs to take care of, but the truth is that this is not brought up again as if nothing happened. In fact, doesn’t Elizabeth have friends and family who care enough about her to miss her for a week? At least one person should notice her intermittent disappearances, since there is a cleaning lady in her house for the first quarter of the movie.

Also, it wouldn’t have hurt to disclose how expensive The Substance is, as it’s unrealistic to think that a company would give away such a product for free. However, if it is indeed free for whatever reason, they sure have one hell of a customer service, considering they even provide the termination serum to stop the process.

With quick cuts borrowed from Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream (2000) and a visual style evocative of Gaspar Noé, along with influences from New French Extremity and David Cronenberg, The Substance portrays Sue’s hedonistic lifestyle and escalating recklessness that accelerates Elizabeth’s aging at an alarming rate. This behavior fuels a bitter conflict between them: Elizabeth hates the toll Sue’s actions take on her, while Sue loathes Elizabeth’s binge eating and ageism, seeing her merely as a source of stabilizer.

So far, the plot bears a striking resemblance to Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, especially when you consider how Elizabeth feels when she looks at the huge picture of herself in her 30s displayed in her lavish Hollywood home, along with the billboard featuring the luscious Sue.

If it were only the other way! If it were I who was to be always young, and the picture that was to grow old! For that—for that—I would give everything! Yes, there is nothing in the whole world I would not give! I would give my soul for that!

— Dorian Gray

Much as Dorian Gray would give away his soul to remain forever young, Elizabeth follows his path in exchange for unexpectedly becoming something akin to the Hunchback of Notre Dame. Realizing how far her thirst for youth and notoriety has taken her, she decides to end it by ordering a termination serum to eliminate her younger self. Yet the process proves more complicated than anticipated, as Elizabeth projects everything she craves onto Sue: recognition, love, cheers, and flashing lights. This realization stirs a sense of remorse that makes her halt the process, understanding that ending Sue would imply destroying the successful part of herself. Though she pauses before injecting the full dose, Sue remains unresponsive. In a desperate effort to bring her back, Elizabeth switches bodies with Sue, causing both to become conscious at once.

Unfortunately, despite the intriguing conflict between the two personas and the numerous ways Fargeat could have explored this idea, she sidelines its psychological dimensions in favor of a physical showdown that turns the scene into a martial arts parody. From this moment on, both The Substance and Elizabeth go off the rails; the constant vacillation between satire with touches of black comedy and body horror commentary on how aging turns women into something bestial to be hidden away is completely torn to shreds to be morphed into a hilarious gore-fest that seeks shock value. Up to this point, reactions in the theater were mixed: some people were scrolling through TikTok (for reasons I can’t fathom), others buried their heads in their knees in disgust, and some, like my friends and I, laughed harder than we had in a long time.

The crux of this absurd arc revolves around Sue’s appointment as host of the New Year’s special. Having killed the matrix in their earlier confrontation, she soon begins to face the consequences as she prepares for her big night in the studio. Her body deteriorates rapidly—even her ears fall off—and in a desperate attempt to stop the decay, she uses the remaining activator serum once more, despite the supplier’s stern warnings. This results in the creation of a grotesque, Picassoesque creature that calls itself Monstro Elisasue. Kudos to Pierre-Olivier Persin and his team for not only creating this abomination, but also for the astonishing prosthetics and make-up effects used extensively throughout the film.

Monstro Elisasue arrives at the live broadcast in full costume, wearing a makeshift mask crafted from a portrait of Elisabeth in her heyday. It strides onto the stage to the dramatic notes of Richard Strauss’ “Thus Spake Zarathustra”—better known as that piece of orchestral music from 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968). For a moment, the audience stares at it in shock without doing anything, as if seeing such a god-awful monster was as common as dirt. After a tense pause, a woman finally screams, triggering the crowd into a chaotic frenzy. The madness escalates when a man from the audience decapitates the monster, leaving everyone covered in blood in a rendition of the infamous scene from Carrie (Brian de Palma, 1976). The entire sequence is one of the funniest I’ve seen in recent memory.

The film’s intro focuses on Elizabeth Sparkle’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, briefly illustrating the inevitable fading of glory and glamour. This serves as an existentialist, Faustian reflection on how, despite our achievements, the inexorable passage of time will eventually erase us from people’s memories. The intro closes with a ketchup-laden hamburger dropping onto the star—a subtle and poetic foreshadowing of Elisabeth’s fate, as she ultimately dies and dissolves in the very place that symbolized the creation of the fame-driven monster that consumed her. This final scene comes full circle with the intro, echoing the tone of the ending of Black Swan (Darren Aronofsky, 2011)—Fargeat certainly draws considerable inspiration from Aronofsky—as it reveals that, at its core, the protagonist’s deepest desire was admiration and acclaim. Like the stain left by the hamburger, the monster’s blood is quickly wiped away, and the world moves on, indifferent to her absence.

From a more atomic perspective, much like Requiem for a Dream or Black Swan, The Substance is not primarily about ageism; rather, it serves as a framework for exploring how people create unrealistic narratives driven by hope, and how such narratives can take hold. In Requiem for a Dream, the vehicle is drug use, while in Black Swan and The Substance, the focus is on the pursuit of public approval. However, the main reason why these pursuits lead to downfall stems from the inability to recognize reality as it is, rather than pursuing her unrealistic expectation of becoming Sue.

Despite the obvious plot holes and my desire for more insight into the psychological struggle between Elizabeth and Sue, I had a blast watching the movie. However, if you’re left with a feeling that resembles mine, I’m sure John Frankenheimer’s Seconds (1966) will scratch your itch for a more narrative-centric film.